Monahism: Diferență între versiuni

(→Originile monahismului creștin) |

|||

| Linia 1: | Linia 1: | ||

| − | |||

{{Traducere EN}} | {{Traducere EN}} | ||

[[Image:Panteleimon_Monastery.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Mănăstirea Sfântul Patelimon, [[Muntele Athos]]]] | [[Image:Panteleimon_Monastery.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Mănăstirea Sfântul Patelimon, [[Muntele Athos]]]] | ||

| Linia 35: | Linia 34: | ||

==Originile monahismului creștin== | ==Originile monahismului creștin== | ||

| + | {{În curs}} | ||

| + | |||

The institution of Christian monasticism began in the deserts in 4th century Egypt as a kind of living [[martyr]]dom. Some scholars attribute the rise of monasticism at this time to the changes in Roman society that had been brought about subsequent to the Emperor St. [[Constantine the Great|Constantine]]'s [[conversion]] and the legal tolerance of Christianity in the Roman Empire. This ended the position of Christians as a small, persecuted group, leading to the rise of nominal Christianity within the Church. In response, many who wished to maintain the intensity of the earliest years of Christian life fled to the desert to [[fasting|fast]] and pray, free from the fragmenting influence of the world. The end of persecution also meant that [[martyr]]dom was no longer as common, and so [[asceticism]] as a form of living martyrdom came to be pursued. | The institution of Christian monasticism began in the deserts in 4th century Egypt as a kind of living [[martyr]]dom. Some scholars attribute the rise of monasticism at this time to the changes in Roman society that had been brought about subsequent to the Emperor St. [[Constantine the Great|Constantine]]'s [[conversion]] and the legal tolerance of Christianity in the Roman Empire. This ended the position of Christians as a small, persecuted group, leading to the rise of nominal Christianity within the Church. In response, many who wished to maintain the intensity of the earliest years of Christian life fled to the desert to [[fasting|fast]] and pray, free from the fragmenting influence of the world. The end of persecution also meant that [[martyr]]dom was no longer as common, and so [[asceticism]] as a form of living martyrdom came to be pursued. | ||

Versiunea de la data 10 ianuarie 2007 21:37

| Acest articol (sau părți din el) este propus spre traducere din limba engleză!

Dacă doriți să vă asumați acestă traducere (parțial sau integral), anunțați acest lucru pe pagina de discuții a articolului. |

| Acest articol face parte din seria Spiritualitate ortodoxă | |

| Sfintele Taine | |

| Botezul – Mirungerea Sf. Împărtășanie – Spovedania Căsătoria – Preoția Sf. Maslu | |

| Starea omului | |

| Păcatul – Patima – Virtutea Raiul – Iadul | |

| Păcate | |

| Păcate strigătoare la cer | |

| Păcate capitale | |

| Alte păcate | |

| Păcatele limbii | |

| Virtuți | |

| Virtuțile teologice | |

| Virtuțile morale Înțelepciunea – Smerenia | |

| Etapele vieții duhovnicești | |

| Despătimirea (Curățirea) Contemplația Îndumnezeirea | |

| Isihasm | |

| Trezvia – Pocăința Isihia – Discernământul Mintea | |

| Asceza | |

| Fecioria – Ascultarea Statornicia – Postul Sărăcia – Monahismul | |

| Rugăciunea | |

| Închinarea – Cinstirea Pravila de rugăciune Rugăciunea lui Iisus Sf. Moaște – Semnul Sf. Cruci | |

| Sfinții Părinți | |

| Părinții apostolici Părinții pustiei Părinții capadocieni Filocalia Scara dumnezeiescului urcuș | |

| Editați această casetă | |

Monahismul (din termenul grec: μοναχος— care înseamnă persoană singură/însingurată) este vechea practică a creștinilor de a părăsi lumea pentru a se închina trup și suflet unei vieți conforme cu Evanghelia, urmărind unirea cu Iisus Hristos.

Scopul monahismului este îndumnezeirea omului (în greacă, theosis), lucrare la care sunt chemați toți creștinii. This ideal is expressed everywhere that the things of God are sought above all other things, as seen for example in the Philokalia, a book of monastic writings. In other words, a monk or nun is a person who has vowed to follow not only the commandments of the Church, but also the counsels (i.e., vows of poverty, chastity, stability, and obedience). The words of Jesus which are the cornerstone for this ideal are "be ye perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect."

Thus, monks practice hesychasm, the spiritual struggle of purification (καθαρσις), illumination (θεωρια) and divinization (θεωσις) in prayer, the sacraments and obedience.

Cuprins

Precursors of the Christian monastic ideal

The ancient models of the modern Christian monastic ideal are the Nazarites and the prophets of Israel. A Nazarite was a person voluntarily separated to the Lord, under a special vow.

- Speak unto the children of Israel, and say unto them, When either man or woman shall separate themselves to vow a vow of a Nazarite, to separate themselves unto the LORD: He shall separate himself from wine and strong drink, and shall drink no vinegar of wine, or vinegar of strong drink, neither shall he drink any liquor of grapes, nor eat moist grapes, or dried. All the days of his separation shall he eat nothing that is made of the vine tree, from the kernels even to the husk. All the days of the vow of his separation there shall no razor come upon his head: until the days be fulfilled, in the which he separateth himself unto the LORD, he shall be holy, and shall let the locks of the hair of his head grow. All the days that he separateth himself unto the LORD he shall come at no dead body. He shall not make himself unclean for his father, or for his mother, for his brother, or for his sister, when they die: because the consecration of his God is upon his head. (Numbers 6:2-8)

The prophets of Israel were set apart to the Lord for the sake of a message of repentance. Some of them lived under extreme conditions, voluntarily separated or forced into seclusion because of the burden of their message. Other prophets were members of communities, schools mentioned occasionally in the Scriptures but about which there is much speculation and little known. The pre-Abrahamic prophets, Enoch and Melchizedek, and especially the Jewish prophets Elijah and his disciple Elisha are important to Christian monastic tradition. The most frequently cited "role-model" for the life of a hermit separated to the Lord, in whom the Nazarite and the prophet are believed to be combined in one person, is John the Baptist. John also had disciples who stayed with him and, as may be supposed, were taught by him and lived in a manner similar to his own:

- In those days came John the Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judaea, And saying, Repent ye: for the kingdom of heaven is at hand. For this is he that was spoken of by the prophet Esaias, saying, The voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths straight. And the same John had his raiment of camel's hair, and a leathern girdle about his loins; and his meat was locusts and wild honey. Then went out to him Jerusalem, and all Judaea, and all the region round about Jordan, And were baptized of him in Jordan, confessing their sins. (Matthew 3:1-6)

The female role models for monasticism are the Theotokos and the four virgin daughters of the Apostle Philip (of the Twelve):

- And when we had finished our course from Tyre, we came to Ptolemais, and saluted the brethren, and abode with them one day. And the next day we that were of Paul's company departed, and came unto Caesarea: and we entered into the house of Philip the evangelist, which was one of the seven; and abode with him. And the same man had four daughters, virgins, which did prophesy. (Acts 21:7-9)

The monastic ideal is also modeled upon the Apostle Paul, who is believed to have been celibate, and a tentmaker:

- For I would that all men were even as I myself. But every man hath his proper gift of God, one after this manner, and another after that. I say therefore to the unmarried and widows, it is good for them if they abide even as I. (I Corinthians 7:7-8)

But the consummate prototype of all Christian monasticism, communal and solitary, is Jesus Christ:

- Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus: Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God: But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men: And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross. (Philippians 2:5-8)

Additionally, the earliest Church was a model for monasticism. The first Christian communities lived in common, sharing everything, according to Acts of the Apostles.

Originile monahismului creștin

| La acest articol se lucrează chiar în acest moment!

Ca o curtoazie față de persoana care dezvoltă acest articol și pentru a evita conflictele de versiuni din baza de date a sistemului, evitați să îl editați până la dispariția etichetei. În cazul în care considerați că este necesar, vă recomandăm să contactați editorul prin pagina de discuții a articolului. |

The institution of Christian monasticism began in the deserts in 4th century Egypt as a kind of living martyrdom. Some scholars attribute the rise of monasticism at this time to the changes in Roman society that had been brought about subsequent to the Emperor St. Constantine's conversion and the legal tolerance of Christianity in the Roman Empire. This ended the position of Christians as a small, persecuted group, leading to the rise of nominal Christianity within the Church. In response, many who wished to maintain the intensity of the earliest years of Christian life fled to the desert to fast and pray, free from the fragmenting influence of the world. The end of persecution also meant that martyrdom was no longer as common, and so asceticism as a form of living martyrdom came to be pursued.

Ss. Anthony and Pachomius were early monastic founders in Egypt, although Paul of Thebes is the very first Christian historically known to have been living as a monk. Orthodoxy also looks to Basil the Great as a founding monastic legislator, as well as the example of the Desert Fathers. St. Benedict of Nursia, who based his own Rule on that of St. Basil, is often credited with being the father of Western monasticism.

From a very early time there were probably individuals who lived a life in isolation—hermits—in imitation of Jesus' 40 days in the desert. They have left no confirmed archaeological traces and only hints in the written record. St. Anthony of Egypt lived as a hermit and developed a following of other hermits who lived nearby but not in community with him. On the other hand, Paul of Thebes lived not very far from Anthony in absolute solitude, and was looked upon even by Anthony as a perfect monk. (When St. Anthony first encountered him, he came away from the experience saying, "Woe is me, my children, a sinful and false monk, who am a monk in name only. I have seen Elijah, I have seen John the Baptist in the desert, and I have seen Paul—in Paradise!") This variety of monasticism is called eremitic ("hermit-like").

St. Pachomius the Great, a follower of Anthony, also acquired a following; he chose to mould them into a community in which the monks lived in individual huts or rooms—cells (from Greek κελλια)—but worked, ate, and worshipped in shared space. This method of monastic organization is called cenobitic ("community-based"). Most monastic life is cenobitic in nature. The head of a monastery came to be known by the word for "Father" in Syriac, Abba—in English, Abbot.

Eventually, a pattern came to be established for some rare monks, having been formed in the communal life, to leave the cenobitic context and undertake the eremetic life. To attempt it without this prior formation is often considered to be spiritual suicide, frequently leading one to fall into prelest, spiritual delusion.

Locul monahismului în societate

Întemeiat în Egipt (cu sfinți ca avva Antonie cel Mare și Pavel Tebeul) și răspândit în Orientul Mijlociu, apoi în Europa, monahismul a rămas una din dimensiunile centrale ale vieții creștine în timpul Evului Mediu occidental și până în perioada târzie a Imperiului Roman de Răsărit (Imperiul Bizantin). Primul loc în care a fost adoptat monahismul în afara celor legate într-un fel sau altul de Roma a fost Irlanda. Aici, monahismul a luat o formă specifică, strâns legată de structura socială tradițională a clanurilor, într-o formă care s-a răspândit mai apoi și în alte părți ale Europei (mai ales în Franța).

Epoca de aur a monahismului creștin a durat cam din secolul al VIII-lea până în secolul al XII-lea d. Hr. Mănăstirile au devenit o parte esențială a societății, luând adesea parte la eforturile de unificare liturgică și la clarificare disputelor doctrinare. Mănăstirile îi atrăgeau pe cei mai buni oameni din societatea acelor vremuri și tot atunci mânăstirile erau principalele păstrătoare și producătoare ale cunoașterii.

În Vest, acest sistem s-a prăbușit în secolele al XI-lea și al XII-lea, ca urmare a transformărilor religioase care au avut loc în acea perioadă. Astfel, creștinismul a încetat progresiv să mai fie apanajul unei elite religioase. Acest lucru s-a datorat în special apariției ordinelor călugărilor cerșetori, cum erau franciscanii, care își propuneau să răspândească învățătura creștină publicului larg, nu doar între zidurile mănăstirilor. Comportamentul religios al oamenilor de rând a început să se schimbe, aceștia începând să ia parte mai des la slujbele și Tainele Bisericii. Presiunea crescândă a statelor naționale și monarhiile timpului au subminat puterea și bogăția ordinelor monahale. În sfărșit, după Conciliul Vatican II, a avut loc un exod masiv al membrilor ordinelor monastice, iar mulți călugări au renunțat să mai poarte haina monahală.În ansamblu, monahismul se află într-o gravă decădere în Biserica Romano-Catolică. Totuși, monahismul a lăsat o puternică amprentă asupra culturii occidentale, amprentă vizibilă și astăzi. Universitățile moderne au încercat să imite monahismul creștin în diferite feluri. Chiar și în Lumea Nouă, unde monahismul nu a fost niciodată o parte obișnuită a vieții sociale, universitățile sunt construite în stilul gotic al mănăstirilor din secolul al XII-lea. Mesele comune, dormitoarele, ritualurile elaborate și uniformele se inspiră extensiv din tradiția monastică.

În Est, monahismul a continuat să se dezvolte și după Marea Schismă din secolul al XI-lea, devenind piatra de hotar și centrul în jurul căruia se puteau strânge creștinii din Imperiul Roman aflat în declin și chiar după Căderea Constantinopolului.

Monahismul ortodox astăzi

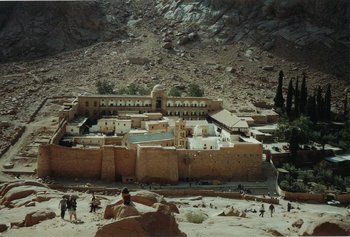

În zilele noastre, monahismul rămâne o parte importantă, esențială a credinței creștin-ortodoxe, iar marile centre monastice precum Muntele Athos și Mănăstirea Sf. Ecaterina din Sinai cunosc astăzi o renaștere, atât din punctul de vedere al numărului de monahi care vin aici, cât și al vieții duhovnicești. Pelerinii sunt din ce în ce mai numeroși, iar reconstrucția mai multora din vechile centre monahale avansează rapid.

Clerul monahal

Monahismul creștin este în sine o rânduială a mirenilor. Călugării nu erau, la origine, asimilați clericilor, ci făceau parte din comunitățile locale (astfel, ei primeau Sfintele Taine de la bisericile parohiale). Totuși, în cazul mănăstirilor izolate, din deșert, cum era cazul obștilor din Egipt, neajunsurile au silit mănăstire fie să accepte preoți ca membri, fie ca starețul sau alți membri ai obștii lor să fie hirotoniți. Un preot-călugăr este numit ieromonah, iar acum ei sunt parte integrantă din viața mânăstirească de obște (comunitară). Există și destul de mulți monahi-diaconi, numiți ierodiaconi

Adesea, în practica ortodoxă, atunci când trebuie hirotonit un episcop pentru o eparhie, candidații sunt monahi de la mănăstirile apropiate. Întrucât majoritatea preoților sunt căsătoriți (înainte de hirotonia pentru treapta de diacon), însă episcopii trebuie să fie celibatari, mănăstirile sunt locuri potrivite de a afla bărbați necăsătoriți care să aibă și maturitatea spirituală necesară, precum și celelalte calități necesare unui ierarh. Mulți sfinți ai Bisericii Ortodoxe sunt exemple ale aceastei practici.

A se vedea și

Legături externe

- Monasticism in the Orthodox Church by Metropolitan Maximos (Aghiorgoussis) of Pittsburgh

- Orthodox Monasticism (Serbian Orthodox Diocese of Raska and Prizren)

- The Ascetic Ideal and the New Testament by Fr. Georges Florovsky

- Orthodox Monasteries Worldwide Directory